The greatest WordPress.com site in all the land!

Of THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS and I

GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS.

The Great Depression of the XXI Century

Global Research, November 20, 2010

2 August 2010

Theme: Global Economy

“This important collection offers the reader a most comprehensive analysis of the various facets – especially the financial, social and military ramifications – from an outstanding list of world-class social thinkers.”

Since the launching of the book in early June, we have been flooded with orders, and excellent reviews continue to come in. This title is available at a special introductory price for Global Research readers for $15.00 plus s&h (list price $25.95).

In all major regions of the world, the economic recession is deep-seated, resulting in mass unemployment, the collapse of state social programs and the impoverishment of millions of people. The meltdown of financial markets was the result of institutionalized fraud and financial manipulation. The economic crisis is accompanied by a worldwide process of militarization, a “war without borders” led by the U.S. and its NATO allies.

This book takes the reader through the corridors of the Federal Reserve, into the plush corporate boardrooms on Wall Street where far-reaching financial transactions are routinely undertaken.

Each of the authors in this timely collection digs beneath the gilded surface to reveal a complex web of deceit and media distortion which serves to conceal the workings of the global economic system and its devastating impacts on people`s lives.

Michel Chossudovsky is an award-winning author, Professor of Economics (Emeritus) at the University of Ottawa and Director of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), Montreal. He is the author of The Globalization of Poverty and The New World Order (2003) and America’s “War on Terrorism” (2005). He is also a contributor to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. His writings have been published in more than twenty languages.

Andrew Gavin Marshall is an independent writer both on the contemporary structures of capitalism as well as on the history of the global political economy. He is a Research Associate with the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

“This important collection offers the reader a most comprehensive analysis of the various facets – especially the financial, social and military ramifications – from an outstanding list of world-class social thinkers.” -Mario Seccareccia, Professor of Economics, University of OttawaThe complex causes as well as the devastating consequences of the economic crisis are carefully scrutinized with contributions from Ellen Brown, Tom Burghardt, Michel Chossudovsky, Richard C. Cook, Shamus Cooke, John Bellamy Foster, Michael Hudson, Tanya Cariina Hsu, Fred Magdoff, Andrew Gavin Marshall, James Petras, Peter Phillips, Peter Dale Scott, Bill Van Auken, Claudia von Werlhof and Mike Whitney.

“In-depth investigations of the inner workings of the plutocracy in crisis, presented by some of our best politico-economic analysts. This book should help put to rest the hallucinations of ‘free market’ ideology.” -Michael Parenti, author of God and His Demons and Contrary Notions

“Provides a very readable exposé of a global economic system, manipulated by a handful of extremely powerful economic actors for their own benefit, to enrich a few at the expense of an ever-growing majority.” -David Ray Griffin, author of The New Pearl Harbor Revisited

Despite the diversity of viewpoints and perspectives presented within this volume, all of the contributors ultimately come to the same conclusion: humanity is at the crossroads of the most serious economic and social crisis in modern history.

“This meticulous, vital, timely and accessible work unravels the history of a hydra-headed monster: military, media and politics, culminating in “humanity at the crossroads”; the current unprecedented economic and social crisis… From the first page of the preface of The Global Economic Crisis, the reasons for all unravel with compelling clarity. For those asking “why?” this book has the answers.” –Felicity Arbuthnot, award-winning author and journalist based in London.The Global Economic Crisis

“The current economic crisis, its causes and hopefully its cure have been a mystery for most people. I welcome a readable exposition of the global dimensions of the crisis and hope for some clarity on how to better organize money locally and internationally for the future.” -Dr. Rosalie Bertell, renowned scientist, Alternative Nobel Prize laureate and Regent, International Physicians for Humanitarian Medicine, Geneva

“This work is much more than a path-breaking and profound historical analysis of the actors and institutions, it is an affirmation of the authors’ belief that a better world is feasible and that it can be achieved by collective organized actions and faith in the sustainability of a democratic order.” -Frederick Clairmonte, distinguished analyst of the global political economy and author of the 1960s classic, The Rise and Fall of Economic Liberalism: The Making of the Economic Gulag

“Decades of profligate economic policies and promiscuous military interventions reached a critical mass, exploding in the meltdown of globalization in 2008. Today, the economic meltdown is reconfiguring everything – global society, economy and culture. This book is engineering a revolution by introducing an innovative global theory of economics.” -Michael Carmichael, prominent author, historian and president of the Planetary Movement

The Great Depression of the XXI Century

Michel Chossudovsky and Andrew Gavin Marshall (Editors)

TO READ THE PREFACE, CLICK HERE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface Michel Chossudovsky and Andrew Gavin Marshall

PART I THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS

Chapter 1 The Global Economic Crisis: An Overview Michel Chossudovsky

Chapter 2 Death of the American Empire Tanya Cariina Hsu

Chapter 3 Financial Implosion and Economic Stagnation John Bellamy Foster and Fred Magdoff

Chapter 4 Depression: The Crisis of Capitalism James Petras

Chapter 5 Globalization and Neoliberalism: Is there an Alternative to Plundering the Earth? Claudia von Werlhof

Chapter 6 The Economy’s Search for a “New Normal” Shamus Cooke

PART II GLOBAL POVERTY

Chapter 7 Global Poverty and the Economic Crisis Michel Chossudovsky

Chapter 8 Poverty and Social Inequality Peter Phillips

PART III WAR, NATIONAL SECURITY AND WORLD GOVERNMENT

Chapter 9 War and the Economic Crisis Michel Chossudovsky

Chapter 10 The “Dollar Glut” Finances America’s Global Military Build-Up Michael Hudson

Chapter 11 Martial Law, the Financial Bailout and War Peter Dale Scott

Chapter 12 Pentagon and Intelligence Black Budget Operations Tom Burghardt

Chapter 13 The Economic Crisis “Threatens National Security” in America Bill Van Auken

Chapter 14 The Political Economy of World Government Andrew Gavin Marshall

PART IV THE GLOBAL MONETARY SYSTEM

Chapter 15 Central Banking: Managing the Global Political Economy Andrew Gavin Marshall

Chapter 16 The Towers of Basel: Secretive Plan to Create a Global Central Bank Ellen Brown

Chapter 17 The Financial New World Order: Towards A Global Currency Andrew Gavin Marshall

Chapter 18 Democratizing the Monetary System Richard C. Cook

PART V THE SHADOW BANKING SYSTEM

Chapter 19 Wall Street’s Ponzi Scheme Ellen Brown,

Chapter 20 Securitization: The Biggest Rip-off Ever Mike Whitney

Purchase the Global Economic Crisis. The Great Depression of the XXI Century, Michel Chossudovsky and Andrew Gavin Marshall (Editors)

About the author:

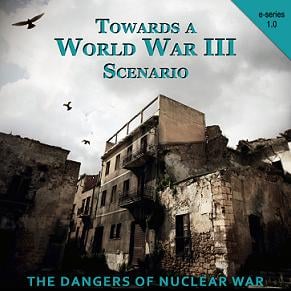

Michel Chossudovsky is an award-winning author, Professor of Economics (emeritus) at the University of Ottawa, Founder and Director of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), Montreal and Editor of the globalresearch.ca website. He is the author of The Globalization of Poverty and The New World Order (2003) and America’s “War on Terrorism”(2005). His most recent book is entitled Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War (2011). He is also a contributor to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. His writings have been published in more than twenty languages.Disclaimer: The contents of this article are of sole responsibility of the author(s). The Centre for Research on Globalization will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. The Center of Research on Globalization grants permission to cross-post original Global Research articles on community internet sites as long as the text & title are not modified. The source and the author’s copyright must be displayed. For publication of Global Research articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: publications@globalresearch.ca

www.globalresearch.ca contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

www.globalresearch.ca contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

Copyright © Prof Michel Chossudovsky and Andrew Gavin Marshall, Global Research, 2010

Robber Barons, Revolution, and Social Control

The Century of Social Engineering, Part 1

Region: USA

Theme: Culture, Society & History

In Part 1 of this series, “The Century of Social Engineering,” I briefly document the economic, political and social background to the 20th century in America, by taking a brief look at the major social upheavals of the 19th century. For an excellent and detailed examination of this history, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (which provided much of the research for this article) is perhaps the most expansive and detailed examination. I am not attempting to serve it justice here, as there is much left out of this historically examination than there is included. The purpose of this essay is to examine first of all the rise of class and labour struggle throughout the United States in the 19th century, the rise and dominance of the ‘Robber Baron’ industrialists like J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller, their convergence of interests with the state, and finally to examine the radical new philosophies and theories that arose within the radicalized and activated populations, such as Marxism and Anarchism. I do not attempt to provide exhaustive or comprehensive analyses of these theoretical and philosophical movements, but rather provide a brief glimpse to some of the ideas (particularly those of anarchism), and place them in the historical context of the mass struggles of the 19th century.

America’s Class Struggle

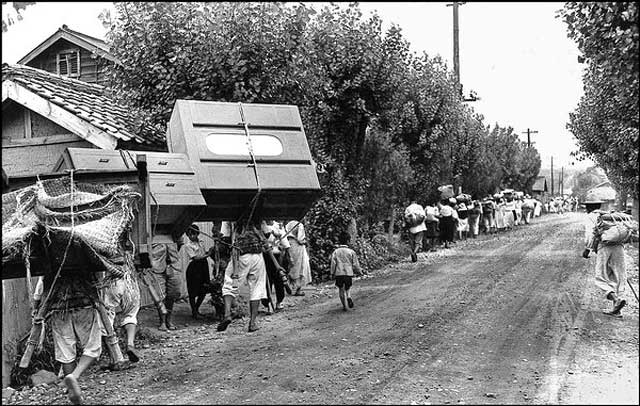

Unbeknownst to most Americans – and for that matter, most people in general – the United States in the 19th century was in enormous upheaval, following on the footsteps of the American Revolution, a revolution which was directed by the landed elite in the American colonies, a new revolutionary spirit arose in the working class populace. The 19th century, from roughly the 1830s onwards, was one great long labour struggle in America.

In the early decades of the 19th century, Eastern capitalists in America began to expand to the West, “and it became important to keep that new West, tumultuous and unpredictable, under control.”[1] The new capitalists favoured monopolization over competition as a method of achieving ‘stability’ and “security to your own property.” The state played its traditional role in securing business interests, as state legislatures gave charters to corporations, granting them legal charters, and “between 1790 and 1860, 2,300 corporations were chartered.”[2] However, as Howard Zinn wrote in A People’s History of the United States:

The attempts at political stability, at economic control, did not quite work. The new industrialism, the crowded cities, the long hours in the factories, the sudden economic crises leading to high prices and lost jobs, the lack of food and water, the freezing winters, the hot tenements in the summer, the epidemics of disease, the deaths of children – these led to sporadic reactions from the poor. Sometimes there were spontaneous, unorganized uprisings against the rich. Sometimes the anger was deflected into racial hatred for blacks, religious warfare against Catholics, nativist fury against immigrants. Sometimes it was organized into demonstrations and strikes.[3]

In the 1830s, “episodes of insurrection” were taking place amid the emergence of unions. Throughout the century, it was with each economic crisis that labour movements and rebellious sentiments would develop and accelerate. Such was the case with the 1837 economic crisis, caused by the banks and leading to rising prices. Rallies and meetings started taking place in several cities, with one rally numbering 20,000 people in Philadelphia. That same year, New York experienced the Flour Riot. With a third of the working class – 50,000 people – out of work in New York alone, and nearly half of New York’s 500,000 people living “in utter and hopeless distress,” thousands of protesters rioted, ultimately leading to police and troops being sent in to crush the protesters.[4]

In 1835 there had been a successful general strike in Philadelphia, where fifty trade unions had organized in favour of a ten-hour work day. In this context, political parties began creating divides between workers and lower class people, as antagonisms developed between many Protestants and Catholics. Thus, middle class politicians “led each group into a different political party (the nativists into the American Republican party, the Irish into the Democratic party), party politics and religion now substituting for class conflict.”[5]

Another economic crisis took place in 1857, and in 1860, a Mechanics Association was formed, demanding higher wages, and called for a strike. Within a week, strikes spread from Lynn, Massachusetts, to towns across the state and into New Hampshire and Maine, “with Mechanics Associations in twenty-five towns and twenty thousand shoe-workers on strike,” marking the largest strike prior to the Civil War.[6] Yet, “electoral politics drained the energies of the resisters into the channels of the system.” While European workers were struggling for economic justice and political democracy, American workers had already achieved political democracy, thus, “their economic battles could be taken over by political parties that blurred class lines.”[7]

The Civil War (1861-1865) served several purposes. First of all, the immediate economic considerations: the Civil War sought to create a single economic system for America, driven by the Eastern capitalists in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, uniting with the West against the slave-labour South. The aim was not freedom for black slaves, but rather to end a system which had become antiquated and unprofitable. With the Industrial Revolution driving people into cities and mechanizing production, the notion of slavery lost its appeal: it was simply too expensive and time consuming to raise, feed, house, clothe and maintain slaves; it was thought more logical and profitable (in an era obsessed with efficiency) to simply pay people for the time they engage in labour. The Industrial Revolution brought with it the clock, and thus time itself became a commodity. As slavery was indicative of human beings being treated as commodities to be bought and sold, owned and used, the Industrial Revolution did not liberate people from servitude and slavery, it simply updated the notions and made more efficient the system of slavery: instead of purchasing people, they would lease them for the time they can be ‘productive’.

Living conditions for the workers and the vast majority, however, were not very different from the conditions of slavery itself. Thus, as the Civil War was sold to the public on the notion of liberating the slaves in the South, the workers of the North felt betrayed and hateful that they must be drafted and killed for a war to liberate others when they themselves were struggling for liberation. Here, we see the social control methods and reorganizing of society that can take place through war, a fact that has always existed and remains today, made to be even more prescient with the advances in technology. During the Civil War, the class conflict among the working people of the United States transformed into a system where they were divided against each other, as religious and racial divisions increasingly erupted in violence. With the Conscription Act of 1863, draft riots erupted in several Northern U.S. cities, the most infamous of which was the New York draft riots, when for three days mobs of rioters attacked recruiting stations, wealthy homes, destroying buildings and killing blacks. Roughly four hundred people were killed after Union troops were called into the city to repress the riots.[8] In the South, where the vast majority of people were not slave owners, but in fact poor white farmers “living in shacks or abandoned outhouses, cultivating land so bad the plantation owners had abandoned it,” making little more than blacks for the same work (30 cents a day for whites as opposed to 20 cents a day for blacks). When the Southern Confederate Conscription Law was implemented in 1863, anti-draft riots erupted in several Southern cities as well.[9]

When the Civil War ended in 1865, hundreds of thousands of soldiers returned to squalor conditions in the major cities of America. In New York alone, 100,000 people lived in slums. These conditions brought a surge in labour unrest and struggle, as 100,000 went on strike in New York, unions were formed, with blacks forming their own unions. However, the National Labour Union itself suppressed the struggle for rights as it focused on ‘reforming’ economic conditions (such as promoting the issuance of paper money), “it became less an organizer of labor struggles and more a lobbyist with Congress, concerned with voting, it lost its vitality.”[10]

The Robber Barons Against Americans

In 1873, another major economic crisis took place, setting off a great depression. Yet, economic crises, while being harmful to the vast majority of people, increasing prices and decreasing jobs and wages, had the effect of being very beneficial to the new industrialists and financiers, who use crisis as an opportunity to wipe out competition and consolidate their power. Howard Zinn elaborated:

The crisis was built into a system which was chaotic in its nature, in which only the very rich were secure. It was a system of periodic crisis – 1837, 1857, 1873 (and later: 1893, 1907, 1919, 1929) – that wiped out small businesses and brought cold, hunger, and death to working people while the fortunes of the Astors, Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Morgans, kept growing through war and peace, crisis and recovery. During the 1873 crisis, Carnegie was capturing the steel market, Rockefeller was wiping out his competitors in oil.[11]

In 1877, a nation-wide railroad strike took place, infuriating the major railroad barons, particularly J.P. Morgan, offered to lend money to pay army officers to go in and crush the strikes and get the trains moving, which they managed to accomplish fairly well. Strikes took place and soldiers were sent in to Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Indiana, with the whole city of Philadelphia in uproar, with a general strike emerging in Pittsburgh, leading to the deployment of the National Guard, who often shot and killed strikers. When all was said and done, a hundred people were dead, a thousand people had gone to jail, 100,000 workers had gone on strike, and the strikes had roused into action countless unemployed in the cities.[12] Following this period, America underwent its greatest spur of economic growth in its history, with elites from both North and South working together against workers and blacks and the majority of people:

They would do it with the aid of, and at the expense of, black labor, white labor, Chinese labor, European immigrant labor, female labor, rewarding them differently by race, sex, national origin, and social class, in such a way as to create separate levels of oppression – a skillful terracing to stabilize the pyramid of wealth.[13]

The bankers and industrialists, particularly Morgan, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Mellon and Harriman, saw enormous increases in wealth and power. At the turn of the century, as Rockefeller moved from exclusively interested in oil, and into iron, copper, coal, shipping, and banking (with Chase Manhattan Bank, now J.P. Morgan Chase), his fortune would equal $2 billion. The Morgan Group also had billions in assets.[14] In 1900, Andrew Carnegie agreed to sell his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $492 million.[15]

Public sentiment at this time, however, had never been so anti-Capitalist and spiteful of the great wealth amassed at the expense of all others. The major industrialists and bankers firmly established their control over the political system, firmly entrenching the two party system through which they would control both parties. Thus, “whether Democrats or Republicans won, national policy would not change in any important way.”[16] Labour struggles had continued and exacerbated throughout the decades following the Civil War. In 1893, another economic depression took place, and the country was again plunged into social upheaval.

The Supreme Court itself was firmly overtaken by the interests of the new elite. Shortly after the Fourteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution to protect newly freed blacks, the Supreme Court began “to develop it as a protection for corporations,” as corporate lawyers argued that corporations were defined as legal ‘persons’, and therefore they could not have their rights infringed upon as stipulated in the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court went along with this reasoning, and even intervened in state legislative decisions which instead promoted the rights of workers and farmers. Ultimately, “of the Fourteenth Amendment cases brought before thee Supreme Court between 1890 and 1910, nineteen dealt with the Negro, 288 dealt with corporations.”[17]

It was in this context that increasing social unrest was taking place, and thus that new methods of social control were becoming increasingly necessary. Among the restless and disgruntled masses, were radical new social theories that had emerged to fill a void – a void which was created by the inherent injustice of living in a human social system in which there is a dehumanizing power structure.

Philosophies of Liberation and Social Dislocation

It was in this context that new theories and philosophies emerged to fill the void created by the hegemonic ideologies and the institutions which propagate them. While these various critical philosophies expanded human kind’s understanding of the world around them, they did not emerge in a vacuum – that is, separate from various hegemonic ideas, but rather, they were themselves products of and to varying degrees espoused certain biases inherent in the hegemonic ideologies. This arose in the context of increasing class conflict in both the United States and Europe, brought about as a result of the Industrial Revolution. Two of the pre-eminent ideologies and philosophies that emerged were Marxism and Anarchism.

Marxist theory, originating with German philosopher Karl Marx, expanded human kind’s understanding of the nature of capitalism and human society as a constant class struggle, in which the dominant class (the bourgeoisie), who own the means of production (industry) exploit the lower labour class (proletariat) for their own gain. Within Marxist theory, the state itself was seen as a conduit through which economic powers would protect their own interests. Marxist theory espoused the idea of a “proletarian revolution” in which the “workers of the world unite” and overthrow the bourgeoisie, creating a Communist system in which class is eliminated. However, Karl Marx articulated a concept of a “dictatorship of the proletariat” in which upon seizing power, the proletariat would become the new ruling class, and serve its own interests through the state to effect a transition to a Communist society and simultaneously prevent a counterrevolution from the bourgeoisie. Karl Marx wrote in the Communist Manifesto (1848) also on the need for a central bank to manage the monetary system. These concepts led to significant conflict between Marxist and Anarchist theorists.

Anarchism is one of the most misunderstood philosophies in modern historical thought, and with good reason: it’s revolutionary potential was boundless, as it was an area of thought that was not as rigid, doctrinaire or divisive as other theories, both hegemonic and critical. No other philosophy or political theory had the potential to unite both socialists and libertarians, two seemingly opposed concepts that found a home within the wide spectrum of anarchist thought, leading to a situation in which many anarchists refer to themselves as ‘libertarian socialists.’ As Nathan Jun has pointed out:

[A]narchism has never been and has never aspired to be a fixed, comprehensive, self-contained, and internally consistent system of ideas, set of doctrines, or body of theory. On the contrary, anarchism from its earliest days has been an evolving set of attitudes and ideas that can apply to a wide range of social, economic, and political theories, practices, movements, and traditions.[18]

Susan Brown noted that within Anarchist philosophy, “there are mutualists, collectivists, communists, federalists, individualists, socialists, syndicalists, [and] feminists,” and thus, “Anarchist political philosophy is by no means a unified movement.”[19] The word “anarchy” is derived from the Greek word anarkhos, which means “without authority.” Thus, anarchy “is committed first and foremost to the universal rejection of coercive authority,” and that:

[C]oercive authority includes all centralized and hierarchical forms of government (e.g., monarchy, representative democracy, state socialism, etc.), economic class systems (e.g., capitalism, Bolshevism, feudalism, slavery, etc.), autocratic religions (e.g., fundamentalist Islam, Roman Catholicism, etc.), patriarchy, heterosexism, white supremacy, and imperialism.[20]

The first theorist to describe himself as anarchist was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a French philosopher and socialist who understood “equality not just as an abstract feature of human nature but as an ideal state of affairs that is both desirable and realizable.”[21] While this was a common concept among socialists, anarchist conceptions of equality emphasized that, “true anarchist equality implies freedom, not quantity. It does not mean that every one must eat, drink, or wear the same things, do the same work, or live in the same manner. Far from it: the very reverse in fact,” as “individual needs and tastes differ, as appetites differ. It is equal opportunity to satisfy them that constitutes true equality.”[22]

Mikhail Bakunin, one of the most prominent anarchist theorists in history, who was also Karl Marx’s greatest intellectual challenger and opposition, explained that individual freedom depends upon not only recognizing, but “cooperating in [the] realization of others’ freedom,” as, he wrote:

My freedom… is the freedom of all since I am not truly free in thought and in fact, except when my freedom and my rights are confirmed and approved in the freedom and rights of all men and women who are my equals.[23]

Anarchists view representative forms of government, such as Parliamentary democracies, with the same disdain as they view overtly totalitarian structures of government. The reasoning is that:

In the political realm, representation involves divesting individuals and groups of their vitality—their power to create, transform, and change themselves. To be sure, domination often involves the literal destruction of vitality through violence and other forms of physical coercion. As a social-physical phenomenon, however, domination is not reducible to aggression of this sort. On the contrary, domination operates chiefly by “speaking for others” or “representing others to themselves”—that is, by manufacturing images of, or constructing identities for, individuals and groups.[24]

Mikhail Bakunin wrote that, “Only individuals, united through mutual aid and voluntary association, are entitled to decide who they are, what they shall be, how they shall live.” Thus, with any hierarchical or coercive institutions, the natural result is oppression and domination, or in other words, spiritual death.[25]

Anarchism emerged indigenously and organically in America, separate from its European counterparts. The first anarchists in America could be said to be “the Antinomians, Quakers, and other left-wing religious groups who found the authority, dogma, and formalism of the conventional churches intolerable.” These various religious groups came to develop “a political outlook which emphasized the anti-libertarian nature of the state and government.” One of the leaders of these religious groups, Adin Ballou, declared that “the essence of Christian morality is the rejection of force, compromise, and the very institution of government itself.” Thus, a Christian “is not merely to refrain from committing personal acts of violence but is to take positive steps to prevent the state from carrying out its warlike ambitions.”[26] This development occurred within the first decades of the 19th century in America.

In the next phase of American philosophical anarchism, inspiration was drawn from the idea of individualism. Josiah Warren, known as the “first American anarchist,” had published the first anarchist periodical in 1833, the Peaceful Revolutionist. Many others joined Warren in identifying the state as “the enemy” and “maintaining that the only legitimate form of social control is self-discipline which the individual must impose upon himself without the aid of government.” Philosophical anarchism grew in popularity, and in the 1860s, two loose federations of anarchists were formed in the New England Labor Reform League and the American Labor Reform League, which “were the source of radical vitality in America for several decades.” American anarchists were simultaneously developing similar outlooks and ideas as Proudhon was developing in Europe. One of the most prominent American anarchists, Benjamin Tucker, translated Proudhon’s work in 1875, and started his own anarchist journals and publications, becoming “the chief political theorist of philosophical anarchism in America.”[27]

Tucker viewed anarchism as “a rejection of all formalism, authority, and force in the interest of liberating the creative capacities of the individual,” and that, “the anarchist must remove himself from the arena of politics, refusing to implicate himself in groups or associations which have as their end the control or manipulation of political power.” Thus, Tucker, like other anarchists, “ruled out the concepts of parliamentary and constitutional government and in general placed himself and the anarchist movement outside the tradition of democracy as it had developed in America.” Anarchism has widely been viewed as a violent philosophy, and while that may be the case for some theorists and adherents, many anarchist theorists and philosophies rejected the notion of violence altogether. After all, its first adherents in America were driven to anarchist theory simply as a result of their uncompromising pacifism. For the likes of Tucker and other influential anarchist theorists, “the state, rather than being a real structure or entity, is nothing more than a conception. To destroy the state then, is to remove this conception from the mind of the individual.” Thus, the act of revolution “has nothing whatever to do with the actual overthrow of the existing governmental machinery,” and Proudhon opined that, “a true revolution can only take place as mankind becomes enlightened.” Revolution, to anarchists, was not an imminent reality, even though it may be an inevitable outcome:

The one thing that is certain is that revolution takes place not by a concerted uprising of the masses but through a process of individual social reformation or awakening. Proudhon, like Tucker and the native American anarchists, believed that the function of anarchism is essentially educational… The state will be abolished at the point at which people in general have become convinced of its un-social nature… When enough people resist it to the point of ignoring it altogether, the state will have been destroyed as completely as a scrap of paper is when it is tossed into a roaring fire.[28]

In the 1880s, anarchism was taken up by many of the radical immigrants coming into America from Europe, such as Johann Most and Emma Goldman, a Jewish Russian feminist anarchist. The press portrayed Goldman “as a vile and unsavory devotee of revolutionary violence.” Goldman partook in an attempted assassination of Henry C. Frick, an American industrialist and financier, historically known as one of the most ruthless businessmen and referred to as “the most hated man in America.” This was saying something in the era of J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Emma Goldman later regretted the attempted assassination and denounced violence as an anarchist methodology. However, she came to acknowledge a view similar to Kropotkin’s (another principle anarchist philosopher), “that violence is the natural consequence of repression and force”:

The state, in her opinion, sows the seeds of violence when it lends it authority and force to the retardation of social change, thereby creating deep-seated feelings of injustice and desperation in the collective unconscious. “I do not advocate violence, government does this, and force begets force.”[29]

The general belief was that “social violence is never arbitrary and meaningless. There is always a deep-seated cause standing behind every deed.” Thus:

Social violence, she argued, will naturally disappear at the point at which men have learned to understand and accommodate themselves to one another within a dynamic society which truly values human freedom. Until then we can expect to see pent up hostility and frustration of certain individuals and groups explode from time to time with the spontaneity and violence of a volcano.[30]

Thus we have come to take a brief glimpse of the social upheaval and philosophies gripping and spreading across the American (and indeed the European) landscape in the 19th century. As a radical reaction to the revolutionizing changed brought by the Industrial Revolution, class struggle, labor unrest, Marxism and Anarchism arose within a populace deeply unsatisfied, horrifically exploited, living in desperation and squalor, and lighting within them a spark – a desire – for freedom and equality. They were not ideologically or methodologically unified, specifically in terms of the objectives and ends; yet, their enemies were the same. It as a struggle among the people against the prevailing and growing sources of power: the state and Capitalist industrialization. The emergence of corporations in America after the Civil War (themselves a creation of the state), created new manifestations of exploitation, greed and power. The Robber Barons were the personification of ‘evil’ and in fact were quite openly and brazenly ruthless. The notion of ‘public relations’ had not yet been invented, and so the industrialists would openly and violently repress and crush struggles, strikes and protests. The state was, after all, firmly within their grip.

It was this revolutionary fervour that permeated the conniving minds of the rich and powerful within America, that stimulated the concepts of social control, and laid the foundations for the emergence of the 20th century as the ‘century of social engineering.’

In Part 2 of “The Century of Social Engineering,” I will identify new ideas of domination, oppression and social control that arose in response to the rise of new ideas of liberation and resistance in the 19th century. This process will take us through the emergence of the major universities and a new educational system, structure and curriculum, the rise of the major philanthropic foundations, and the emergence of public relations. The combination of these three major areas: education, philanthropy, and public relations (all of which interact and are heavily interdependent), merged and implemented powerful systems of social control, repressing the revolutionary upheaval of the 19th century and creating the conditions to transform American, and in fact, global society in the 20th century.

Andrew Gavin Marshall is a Research Associate with the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG). He is co-editor, with Michel Chossudovsky, of the recent book, “The Global Economic Crisis: The Great Depression of the XXI Century,” available to order at Globalresearch.ca. He is currently working on a forthcoming book on ’Global Government’.

Notes

[1] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (Harper Perennial: New York, 2003), page 219

[2] Ibid, pages 219-220.

[3] Ibid, page 221.

[4] Ibid, pages 224-225.

[5] Ibid, pages 225-226.

[6] Ibid, page 231.

[7] Ibid, page 232.

[8] Ibid, pages 235-236.

[9] Ibid, pages 236-237.

[10] Ibid, pages 241-242.

[11] Ibid, page 242.

[12] Ibid, pages 245-251.

[13] Ibid, page 253.

[14] Ibid, pages 256-257.

[15] Ibid, page 257.

[16] Ibid, page 258.

[17] Ibid, pages 260-261.

[18] Nathan Jun, “Anarchist Philosophy and Working Class Struggle: A Brief History and Commentary,” WorkingUSA: The Journal of Labor and Society (Vol. 12, September 2009), page 505

[19] Ibid, page 506.

[20] Ibid, pages 507-508.

[21] Ibid, page 509.

[22] Ibid, page 510.

[23] Ibid, pages 510-511.

[24] Ibid, page 512.

[25] Ibid, page 512.

[26] William O. Reichert, “Toward a New Understanding of Anarchism,” The Western Political Quarterly (Vol. 20, No. 4, December 1967), page 857.

[27] Ibid, page 858.

[28] Ibid, pages 858-860.

[29] Ibid, pages 860-861.

[30] Ibid, page 862.

Articles by: Andrew Gavin Marshall

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are of sole responsibility of the author(s). The Centre for Research on Globalization will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. The Center of Research on Globalization grants permission to cross-post original Global Research articles on community internet sites as long as the text & title are not modified. The source and the author’s copyright must be displayed. For publication of Global Research articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: publications@globalresearch.ca

www.globalresearch.ca contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

For media inquiries: publications@globalresearch.ca

For media inquiries: publications@globalresearch.ca

Copyright © Andrew Gavin Marshall, Global Research, 2011

Michel Chossudovsky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Michel Chossudovsky (born 1946) is a Canadian economist.

He is professor of economics (emeritus) at the University of Ottawa. Chossudovsky has been a visiting professor internationally, and has been an advisor to governments of developing countries. In 1999, Chossudovsky joined the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research as an adviser.[1] Chossudovsky is a signatory of the Kuala Lumpur declaration to criminalize war. He is the author of The Globalization of Poverty and The New World Order (2003) and America’s “War on Terrorism” (2005) and Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War (2011).[1][2][3][4]

Based at the University of Ottawa from 1968 he is founder, editor, and director of the Centre for Research on Globalisation (CRG), located in Montreal, Canada. It is “committed to curbing the tide of globalisation and disarming the new world order“.[5][verification needed] CRG maintains the website GlobalResearch.ca which is critical of United States foreign policy and NATO, as well as theories concerning the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the war on terror, media disinformation, poverty and social inequality, the global economic crisis, and politics and religion. Chossudovsky was profiled in the Ottawa Citizen in an article by Juliet O’Neill.[6]

On the internationally available Russian station RT in 2010, he stated that U.S. President Barack Obama, not Osama bin Laden, is the biggest threat to global security.[22] In the Preface of America’s “War on Terrorism” he wrote:

In Mike Karadjis’ 2000 book Bosnia, Kosova, and the West, Chossudovsky is referred to as a “pro-Milošević leftist”, as well as accused of “systematically distorting events in Albania and the wars in the Balkans in the 1990s”.[25]

In a 2006 op-ed by Terry O’Neill in the conservative Canadian news magazine, Western Standard, Chossudovsky was included on the list of “Canada’s nuttiest professors, those whose absurdity stands head and shoulders above their colleagues.”[27] Listed alongside Chossudovsky were Sunera Thobani, Shannon Bell, John McMurtry, Shadia Drury, Michael Keefer,[28]Taiaiake Alfred, Leo Panitch, Kathleen Mahoney, Thomas Homer-Dixon, Sophie Quigley, and Joel Bakan. Specifically, the op-ed referred to GlobalResearch.ca as “anti-U.S. and anti-globalization”[27] and criticized Chussodovsky’s thesis and views — namely: that the U.S. had knowledge of the 911 attacks before they happened; that Washington had weapons that could influence climate change; and lastly, that the large banking institutions are the cause of the collapse of smaller economies — as “wild-eyed conspiracy theories”.[27]

He is professor of economics (emeritus) at the University of Ottawa. Chossudovsky has been a visiting professor internationally, and has been an advisor to governments of developing countries. In 1999, Chossudovsky joined the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research as an adviser.[1] Chossudovsky is a signatory of the Kuala Lumpur declaration to criminalize war. He is the author of The Globalization of Poverty and The New World Order (2003) and America’s “War on Terrorism” (2005) and Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War (2011).[1][2][3][4]

Contents |

Biography

Chossudovsky is the son of the academician, Russian born Evgeny Chossudovsky (1914–2006) and Rachel, from Northern Ireland. Raised in Geneva, he is a graduate of the University of Manchester, and obtained a PhD at the University of North Carolina.Based at the University of Ottawa from 1968 he is founder, editor, and director of the Centre for Research on Globalisation (CRG), located in Montreal, Canada. It is “committed to curbing the tide of globalisation and disarming the new world order“.[5][verification needed] CRG maintains the website GlobalResearch.ca which is critical of United States foreign policy and NATO, as well as theories concerning the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the war on terror, media disinformation, poverty and social inequality, the global economic crisis, and politics and religion. Chossudovsky was profiled in the Ottawa Citizen in an article by Juliet O’Neill.[6]

Writings

Global economic crisis

Chossudovsky believes that the 2007–2012 global economic crisis was caused by deliberate fraud perpetuated by powerful institutions. This coupled with increased militarization around the world is contributing to mass unemployment, global poverty and decrease of government social programs.[7] He predicted in 1998 that “the late 20th century will go down in world history as a period of global impoverishment marked by the collapse of productive systems in the developing world, the demise of national institutions and the disintegration of health and education programs.”[8]HAARP

Chossudovsky argues that from a military standpoint, the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP) is an operational weapon of mass destruction with the potential to be used against “rogue states”, with the power to alter the weather, disrupt regional electrical power systems, and modify the Earth’s magnetic field, as well as potentially trigger earthquakes and affect people’s health. Chossudovsky stated that the policy guidelines already contain weather intervention techniques and that the technology has finished its final stages of development according to an interview with physicist Bernard Eastlund in 1997.[9][10][11] He explains that these techniques are not a new concept and that mathematician, John von Neumann, had begun research on the topic in the late 1940s in coordination with the U.S. Department of Defense.[12]IMF

Chossudovsky asserts that Dominique Strauss-Kahn was framed with sexual assault charges by powerful members of the financial establishment in order to install a more compliant leader. Dominique Strauss-Kahn was pushing for reforms within the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[13]Libya

Chossudovsky asserted at the outset of the Libya conflict that this was part of a larger agenda for corporate interests to take over 60% of the world’s oil reserves.[14] He has written that the rebels of Libya, who formed an alliance with NATO, were former members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and that this same group was listed as a bona fide terrorist organization with the United Nations Security Council.[15][16]Syria

Chossudovsky asserts that the protestors against the government regime are covertly supported by western intelligence and are the cause of the unrest in Syria. He claims the western media shows bias in their reporting by not showing the evidence of massive support for Assad shown in a rally on March 29, 2011 in Damascus and claims that there are Assad forces that are also being killed, which he says is also ignored.[17]Swine flu

Chossudovsky has argued that reports released in the British press regarding the plans for mass morgues due to H1N1 were totally fabricated and that “the British government is deliberately misleading the British public”, claiming that there were reports from Britain’s Health Protection Agency that confirmed that the proposed vaccines would be more deadly than the disease.[18]Terrorism

After the September 11 attacks he highlighted the historical relationship between the US government, Bin Laden and Al Qaeda. He asserted in 2004 that the invasion of Afghanistan had long been planned by the United States and NATO, with the 9/11 attacks used as an excuse to justify the war.[19][20] In a speech given at the Perdana Global Peace Forum in 2005, Chossudovsky stated that “Osama bin Laden and the Taliban were identified as the prime suspects of the 9/11 attacks, without a shred of evidence” and that “Amply documented, the war on terrorism is a fabrication.”[21]On the internationally available Russian station RT in 2010, he stated that U.S. President Barack Obama, not Osama bin Laden, is the biggest threat to global security.[22] In the Preface of America’s “War on Terrorism” he wrote:

The myth of the “outside enemy” and the threat of “Islamic terrorists” was the cornerstone of the Bush administration’s military doctrine, used as a pretext to invade Afghanistan and Iraq, not to mention the repeal of civil liberties and constitutional government in America. Without an “outside enemy”, there could be no “war on terrorism”.[23]

Yugoslavia

Chossudovsky has questioned the widespread notion that the Yugoslav Wars were primarily motivated by ethnic or nationalist conflict. In his 1996 article “Dismantling Yugoslavia: Colonizing Bosnia”, he wrote that the macroeconomic restructuring and the deep-seated economic crisis of the 1980s helped destroy Yugoslavia, but that the global media have carefully overlooked or denied the central role of Western-backed neoliberal policies in the process, and that after the war the Western powers have concentrated on debt repayment and potential energy bonanzas rather than rebuilding the economy.[24]In Mike Karadjis’ 2000 book Bosnia, Kosova, and the West, Chossudovsky is referred to as a “pro-Milošević leftist”, as well as accused of “systematically distorting events in Albania and the wars in the Balkans in the 1990s”.[25]

Criticism

A 2005 article in The Jewish Tribune has criticized GlobalResearch.ca as “rife with anti-Jewish conspiracy theory and Holocaust denial.” B’nai Brith Canada had complained that there were comments on a forum moderated by Chossudovsky that questioned how many Jews died in the holocaust. Chossudovsky responded that there was a disclaimer that the website was not to be held responsible for the views expressed in the forum, and he had the comment removed. He also said that he was of Jewish heritage and would be one of the last people to condone antisemitic views.[26] The same article also reported that B’nai Brith Canada wrote a letter to the University of Ottawa asking for the university “to conduct its own investigation of this propagandist site.”[26]In a 2006 op-ed by Terry O’Neill in the conservative Canadian news magazine, Western Standard, Chossudovsky was included on the list of “Canada’s nuttiest professors, those whose absurdity stands head and shoulders above their colleagues.”[27] Listed alongside Chossudovsky were Sunera Thobani, Shannon Bell, John McMurtry, Shadia Drury, Michael Keefer,[28]Taiaiake Alfred, Leo Panitch, Kathleen Mahoney, Thomas Homer-Dixon, Sophie Quigley, and Joel Bakan. Specifically, the op-ed referred to GlobalResearch.ca as “anti-U.S. and anti-globalization”[27] and criticized Chussodovsky’s thesis and views — namely: that the U.S. had knowledge of the 911 attacks before they happened; that Washington had weapons that could influence climate change; and lastly, that the large banking institutions are the cause of the collapse of smaller economies — as “wild-eyed conspiracy theories”.[27]

Bibliography

- With Fred Caloren and Paul Gingrich, Is the Canadian Economy Closing Down? (Montreal: Black Rose, 1978) ISBN 0-919618-80-4

- Towards Capitalist Restoration? Chinese Socialism After Mao (New York: St Martin’s, 1986 and London: Macmillan, 1986) ISBN 0-333-38441-5

- The Globalization of Poverty: Impacts of IMF and World Bank Reforms, (Penang: Third World Network, 1997) and (London: Zed, 1997) ISBN 81-85569-34-7 and ISBN 1-85649-402-0

- Exporting Apartheid to Sub-Saharan Africa (New Delhi: Madhyam, 1997) ISBN 81-86816-06-2

- ‘Washington’s New World Order Weapons Can Trigger Climate Change’, (November 26, 2000)

- Guerres et Mondialisation: A Qui Profite Le 11 Septembre? (Serpent a Plume, 2002) ISBN 2-84261-387-2

- The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order (Oro, Ontario: Global Outlook, 2003) ISBN 0-9731109-1-0– Excerpt.

- America’s “War on Terrorism” (Pincourt, Quebec: Global Research, 2005) ISBN 0-9737147-1-9

References

- ^ ab“TFF Associates”. The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research.

- ^ Scott A. Bessenecker (October 31, 2006). The New Friars: The Emerging Movement Serving the World’s Poor. IVP Books. p. 156.

- ^Michel Chossudovsky – Department of Economics. Socialsciences.uottawa.ca. Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^Towards a World War III Scenario. New E-Book from Global Research Publishers. By Prof Michel Chossudovsky. Global Research, June 30, 2011.

- ^“Globalization Links: Anti-Establishmentarians on the Web”. The University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development. June 2002. Retrieved 19 May 2011.[dead link]

- ^Battling Mainstream Economics. By Juliet ONeill.

- ^The Global Economic Crisis. Globalresearch.ca. Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^ Chossudovsky (1998). “Global Poverty in the Late 20th Century”. Journal of International Affairs52. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Michel Chossudovsky, “The Ultimate Weapon of Mass Destruction: ‘Owning the Weather’ for Military Use,” Global Research (27 September 2004).

- ^ Michel Chossudovsky, “H.A.A.R.P. It’s not only greenhouse gas emissions: Washington’s new world order weapons have the ability to trigger climate change.”http://www.FromTheWildrness.com (November 2000)

- ^ Michel Chossudovsky, “Weather Warfare: Beware the US military’s experiments with climatic warfare,” Global Research (December 7, 2007).

- ^Weather warfare. The Ecologist (2008-05-22). Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^Regime Change at the IMF: The Frame-Up of Dominique Strauss-Kahn? [Voltaire Network]. Voltairenet.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^“Operation Libya” and the Battle for Oil: Redrawing the Map of Africa. Globalresearch.ca. Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^The “Liberation” of Libya: NATO Special Forces and Al Qaeda Join Hands. Globalresearch.ca. Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^Foreign Terrorist Organizations – Multimedia Counterterrorism Calendar. Nctc.gov (2011-12-27). Retrieved on 2012-01-08.

- ^“SYRIA: Who is Behind The Protest Movement? Fabricating a Pretext for a US-NATO “Humanitarian Intervention”". Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^“H1N1 October surprise prevention”. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Michel Chossudovsky, “‘Revealing the Lies’ on 9/11 Perpetuates the ‘Big Lie’,” Global Research, 27 May 2004. Text of Michel Chossudovsky’s keynote presentation at the opening plenary session (27 May 2004) to The International Citizens Inquiry Into 9/11, Toronto, 25–30 May 2004.

- ^ Michel Chossudovsky, “9/11 and the “American Inquisition”,” Global Research (September 11, 2008).

- ^The Anglo-American War of Terror: An Overview by Michel Chossudovsky, Global Research, December 21, 2005.

- ^ Chossudovsky, Michel. “April 4, 2010 VIDEO: Obama, not Osama, is Threat No.1 to Global Security by Michel Chossudovsky”. Globalresearch.ca. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ^ Chossudovsky, Michel (2005-09-15). “Preface to the second edition”. America’s “War on Terrorism” (2nd ed.). Global Research. p. XII.

- ^ Chossudovsky, “Dismantling Yugoslavia: Colonizing Bosnia,”Covert Action, No. 56 (Spring 1996).

- ^ Karadjis (2000). Bosnia, Kosova, and the West. pp. 172–178, 207.

- ^ ab“Conspiracy web site by Ottawa Professor sets dangerous examples for students”. Jewish Tribune Canada. 2005-08-25.

- ^ abc Terry O’Niell (2006-09-25). “Canada’s nuttiest professors”. Western Standard.

- ^In Defence of Michel Chossudovsky. By Michael Keefer. September 4, 2005.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Michel Chossudovsky |

- Chossudovsky’s articles at Centre for Research on Globalization

- A list of audio interviews: (French Connection Audio Archive)

- War and Globalization presentation. (Google Video)

Categories (++):

- 1946 births(−)(±)

- Living people(−)(±)

- 9/11 conspiracy theorists(−)(±)

- Alumni of the University of Manchester(−)(±)

- Anti-globalization writers(−)(±)

- Canadian anti-war activists(−)(±)

- Canadian economists(−)(±)

- Canadian non-fiction writers(−)(±)

- Canadian people of Irish descent(−)(±)

- Canadian people of Russian descent(−)(±)

- Canadian socialists(−)(±)

- Conspiracy theorists(−)(±)

- University of Ottawa faculty(−)(±)

- University of North Carolina alumni(−)(±)

- (+)

Categories: UncategorizedLeave a comment

The World is at a critical crossroads. The Fukushima disaster in Japan has brought to the forefront the dangers of Worldwide nuclear radiation.

The World is at a critical crossroads. The Fukushima disaster in Japan has brought to the forefront the dangers of Worldwide nuclear radiation.

AUNG SAN SUU KYI1

AUNG SAN SUU KYI1 THEIN SEIN1

THEIN SEIN1 MONCEF MARZOUKI2

MONCEF MARZOUKI2 BILL CLINTON3

BILL CLINTON3 HILLARY CLINTON3

HILLARY CLINTON3 SEBASTIAN THRUN4

SEBASTIAN THRUN4 BILL GATES5

BILL GATES5 MELINDA GATES5

MELINDA GATES5 MALALA YOUSAFZAI6

MALALA YOUSAFZAI6 BARACK OBAMA7

BARACK OBAMA7 PAUL RYAN8

PAUL RYAN8 CHEN GUANGCHENG9

CHEN GUANGCHENG9 DAVID BLANKENHORN10

DAVID BLANKENHORN10 NARAYANA KOCHERLAKOTA10

NARAYANA KOCHERLAKOTA10 RICHARD A. MULLER10

RICHARD A. MULLER10 JAMES HANSEN11

JAMES HANSEN11 ANGELA MERKEL12

ANGELA MERKEL12 EHUD BARAK13

EHUD BARAK13 BENJAMIN NETANYAHU13

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU13 MEIR DAGAN14

MEIR DAGAN14 YUVAL DISKIN14

YUVAL DISKIN14 BEN BERNANKE15

BEN BERNANKE15 SCOTT SUMNER15

SCOTT SUMNER15 MARIA ALYOKHINA16

MARIA ALYOKHINA16 YEKATERINA SAMUTSEVICH16

YEKATERINA SAMUTSEVICH16 NADEZHDA TOLOKONNIKOVA16

NADEZHDA TOLOKONNIKOVA16 ABRAHAM KAREM17

ABRAHAM KAREM17 WILLIAM MCRAVEN17

WILLIAM MCRAVEN17 AHLEM BELHADJ18

AHLEM BELHADJ18 RIMA DALI19

RIMA DALI19 BASSEL KHARTABIL19

BASSEL KHARTABIL19 MARIO DRAGHI20

MARIO DRAGHI20 GEORGE SOROS21

GEORGE SOROS21 JOYCE BANDA22

JOYCE BANDA22 ED MORSE23

ED MORSE23 THOMAS PIKETTY24

THOMAS PIKETTY24 EMMANUEL SAEZ24

EMMANUEL SAEZ24 NADIM MATTA25

NADIM MATTA25 AI WEIWEI26

AI WEIWEI26 CHRISTINE LAGARDE27

CHRISTINE LAGARDE27 AHMET DAVUTOGLU28

AHMET DAVUTOGLU28 RECEP TAYYIP ERDOGAN28

RECEP TAYYIP ERDOGAN28 WILLEM BUITER29

WILLEM BUITER29 ELON MUSK30

ELON MUSK30 MARISSA MAYER31

MARISSA MAYER31 SHERYL SANDBERG31

SHERYL SANDBERG31 ANNE-MARIE SLAUGHTER32

ANNE-MARIE SLAUGHTER32 SALMAN RUSHDIE33

SALMAN RUSHDIE33 PAUL KRUGMAN34

PAUL KRUGMAN34 NOURIEL ROUBINI35

NOURIEL ROUBINI35 SHAI RESHEF36

SHAI RESHEF36 DAPHNE KOLLER37

DAPHNE KOLLER37 ANDREW NG37

ANDREW NG37 DICK CHENEY38

DICK CHENEY38 LIZ CHENEY38

LIZ CHENEY38 CONDOLEEZZA RICE39

CONDOLEEZZA RICE39 EUGENE KASPERSKY40

EUGENE KASPERSKY40 SIMA SAMAR41

SIMA SAMAR41 DEBBIE BOSANEK42

DEBBIE BOSANEK42 WARREN BUFFETT42

WARREN BUFFETT42 CHARLES MURRAY43

CHARLES MURRAY43 ANDREW MARSHALL44

ANDREW MARSHALL44 ALEXEY NAVALNY45

ALEXEY NAVALNY45 THOMAS MANN46

THOMAS MANN46 NORMAN ORNSTEIN46

NORMAN ORNSTEIN46 MOHAMMAD FAHAD AL-QAHTANI47

MOHAMMAD FAHAD AL-QAHTANI47 ABDULHADI AL-KHAWAJA48

ABDULHADI AL-KHAWAJA48 MARYAM AL-KHAWAJA48

MARYAM AL-KHAWAJA48 ZAINAB AL-KHAWAJA48

ZAINAB AL-KHAWAJA48 NABEEL RAJAB48

NABEEL RAJAB48 HARUKI MURAKAMI49

HARUKI MURAKAMI49 ROBERT KAGAN50

ROBERT KAGAN50 NGOZI OKONJO-IWEALA51

NGOZI OKONJO-IWEALA51 MARTIN FELDSTEIN52

MARTIN FELDSTEIN52 MOHAMED EL-ERIAN53

MOHAMED EL-ERIAN53 YU JIANRONG54

YU JIANRONG54 MICHAEL SANDEL55

MICHAEL SANDEL55 JOHN BRENNAN56

JOHN BRENNAN56 JAMEEL JAFFER57

JAMEEL JAFFER57 BJORN LOMBORG58

BJORN LOMBORG58 HAMAD BIN KHALIFA AL THANI59

HAMAD BIN KHALIFA AL THANI59 HEW STRACHAN60

HEW STRACHAN60 HUSAIN HAQQANI61

HUSAIN HAQQANI61 FARAHNAZ ISPAHANI61

FARAHNAZ ISPAHANI61 ESTHER DUFLO62

ESTHER DUFLO62 KIYOSHI KUROKAWA63

KIYOSHI KUROKAWA63 DARON ACEMOGLU64

DARON ACEMOGLU64 JAMES ROBINSON64

JAMES ROBINSON64 PAUL ROMER65

PAUL ROMER65 ALEXANDER MACGILLIVRAY66

ALEXANDER MACGILLIVRAY66 RUCHIR SHARMA67

RUCHIR SHARMA67 CHINUA ACHEBE68

CHINUA ACHEBE68 MA JUN69

MA JUN69 YEVGENIA CHIRIKOVA70

YEVGENIA CHIRIKOVA70 RAND PAUL71

RAND PAUL71 SRI MULYANI INDRAWATI72

SRI MULYANI INDRAWATI72 WANG JISI73

WANG JISI73 RAJ CHETTY74

RAJ CHETTY74 ASGHAR FARHADI75

ASGHAR FARHADI75 ADELA NAVARRO BELLO76

ADELA NAVARRO BELLO76 NITISH KUMAR77

NITISH KUMAR77 ROGER DINGLEDINE78

ROGER DINGLEDINE78 NICK MATHEWSON78

NICK MATHEWSON78 PAUL SYVERSON78

PAUL SYVERSON78 ELIOT COHEN79

ELIOT COHEN79 RAGHURAM RAJAN80

RAGHURAM RAJAN80 PATRICE MARTIN81

PATRICE MARTIN81 JOCELYN WYATT81

JOCELYN WYATT81 ROBERT D. KAPLAN82

ROBERT D. KAPLAN82 KAI-FU LEE83

KAI-FU LEE83 BETH NOVECK84

BETH NOVECK84 RADOSLAW SIKORSKI85

RADOSLAW SIKORSKI85 PANKAJ MISHRA86

PANKAJ MISHRA86 TARIQ RAMADAN87

TARIQ RAMADAN87 JÜRGEN HABERMAS88

JÜRGEN HABERMAS88 RICKEN PATEL89

RICKEN PATEL89 VIVEK WADHWA90

VIVEK WADHWA90 DANAH BOYD91

DANAH BOYD91 SLAVOJ ZIZEK92

SLAVOJ ZIZEK92 MARTHA NUSSBAUM93

MARTHA NUSSBAUM93 JOHN COATES94

JOHN COATES94 JONATHAN ZITTRAIN95

JONATHAN ZITTRAIN95 LUIGI ZINGALES96

LUIGI ZINGALES96 VIVIANE REDING97

VIVIANE REDING97 JONATHAN HAIDT98

JONATHAN HAIDT98 PETER BEINART99

PETER BEINART99 SANA SALEEM100

SANA SALEEM100